Darkest hour for the men on the Mound

By Ian Fraser, Kenny Kemp and Quentin Sommerville

Published: Sunday Herald

Date: June 6th, 1999

IT will go down in history as Scotland’s worst video nasty. The men on the Mound believed they had weathered the worst of the storm over their controversial deal with television evangelist Pat Robertson. Until last Monday morning, that is.

That was when the Edinburgh-based newspaper the Scotsman, which has been tenacious in covering the story, let rip with another front-page blockbuster. A reporter in its North Bridge newsroom had received a tip-off about Robertson’s thoughts on Scotland. The anonymous caller told the reporter to look at a website.

He did – and downloaded a video of a television broadcast by Robertson in which the right-wing evangelist described Scotland as a “dark land” where homosexuals have “incredibly strong influence”.

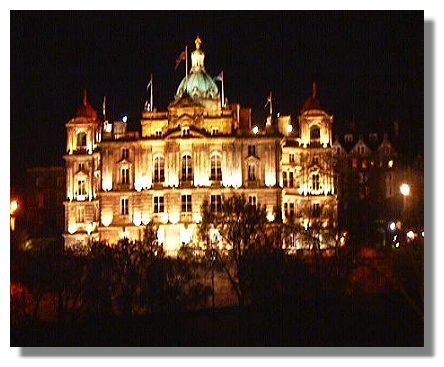

The next morning senior figures gathered in the Georgian boardroom at the Bank of Scotland’s headquarters on the Mound, overlooking Princes Street Gardens, and sat through a videotape of Robertson’s 700 Club programme. They watched in dismay as a loose cannon blew a gaping hole in their global banking strategy – and this time they agreed that their putative partner had gone too far.

The time had come to admit that they had made an enormous blunder. These men – rich, white Scots, all aged over 55 – have presided over one of Scotland’s most successful companies, built on a blend of prudence and innovation.

The bank’s chief executive, Peter Burt, exemplifies the authority of an institution several years older than the Bank of England. He takes pride in being described as “reliable and boring” despite some sharp commercial instincts.

But such admirable Scottish traits, cocooned in an ivory tower which commands the best views of the capital, clearly missed the mark in the wider, rapidly changing world. The bank’s senior executives showed a serious lack of streetwise intelligence by failing to anticipate the public’s alarm at the nature of their chosen partner.

The outcry over Robertson – from students, gay rights campaigners, politicans, trade unionists and even church leaders – stunned them.

It wasn’t long before a siege mentality developed on the Mound, with the paranoid belief that the media, particularly the Scotsman, were out to get them.

Throughout the past few months the bank has continually repeated the line that the deal made excellent financial sense and that Robertson’s views were being misrepresented by the press. The bank’s spin-doctors also claimed that it was dealing with Robertson the businessman, not the outspoken politician or preacher.

But when the Sunday Herald met the American at his sprawling Virginia Beach campus, Robertson rubbished this idea. “I don’t remember being cut in two any time recently,” he said. “They are doing business with a man called Pat Robertson who I understand is a man of integrity and honour – and that flows from my deeply held religious beliefs, so I think it’s all part of one package. It’s not two people.”

Other than this misjudgement, it was two everyday aspects of modern life – the internet and consumers’ growing interest in ethical issues – that conspired to floor the Bank of Scotland. The internet made it possible for almost any casual surfer to witness Robertson’s own websites – as well as the criticisms levelled against him by perfectly respectable liberal organisations.

And on ethical matters, hadn’t the middle classes of the Lothians voted in the first Green member of a British parliament?

While the deal was originally welcomed by the City, it soon caused outrage. Protesters chained themselves to railings outside the bank, and the TUC threatened to withdraw from an arrangement which provided 100,000 of its members with Bank of Scotland affinity credit cards. The University of Edinburgh, Shetlands Council, the new Scottish Parliament and West Lothian Council also reviewed their relations with the Mound.

The bank now admits that it had not done its homework properly. It had looked at the deal through the wrong end of the telescope, seeing it as a wonderful financial opportunity without realising how it appeared to more liberal-minded people.

Even yesterday morning Ned Sherrin, the satirist on Radio 4’s Loose Ends show, was mocking the Bank of Scotland for its stupidity. And in London, sophisticated metropolitan types were taking free pot-shots at the bank.

So the Tuesday morning meeting was a watershed. Peter Watson, a Glasgow lawyer and the tele-evangelist’s legal representative and spokesman in Scotland, went into a smaller room adjacent to the meeting room and called the preacher.

He told Robertson: “The bank is on fire. The Scottish press are on fire” – and said the share price was plummeting. He suggested an immediate meeting. Robertson shrugged, saying he didn’t have the time since he was on a fundraising roadshow to acquire an oil refinery. Watson pleaded, and Robertson reluctantly agreed to a meeting with Burt and the bank’s officials. “Boston on Friday,” he said.

Burt, the man who had only months earlier welcomed Robertson as a good Presbyterian, immediately accepted. Jack Irvine, the PR streetfighter brought in to manage the crisis, would accompany him to the meeting along with international general manager Colin McGill. Meanwhile, word went out that the deal was dead in the water.

Burt, accompanied by Irvine and the bank’s lawyers, flew out to Massachusetts. The meeting began with warm handshakes at 5.15pm local time last Friday in the executive meeting rooms of Logan Airport in Boston. Outside on the runway, Hillary Clinton’s Airforce Two was ready for take-off.

Robertson was accompanied by Watson, his improbable sounding US attorney Nelson Happy, and an accountant. The three men’s meeting with Burt, McGill and Irvine was convivial, although little progress had been made when Robertson left for Virginia in his private Gulfstream jet two hours later.

At 9.30pm the men reconvened by teleconference and worked into the early hours of the morning before reaching a final deal. Despite earlier assurances that no compensation would be made to Robertson, the bank agreed to pay an undisclosed sum to the preacher to buy out his share of partnership. Robertson, according to one insider, was saddened by the cultural divide which had led to the collapse of the deal, and expressed his love for Scotland and the Scottish people.

When the deal was first announced on March 2, he had said: “It is a very nice coincidence that my forebears left Scotland in 1695, the year in which Bank of Scotland was founded.” Whether the personal friendship between Robertson and Burt will continue remains to be seen.

As the US attorneys went off to draft the words for Robertson’s signature, Irvine and his colleagues returned to Room 355 of the Meridien Hotel to send a satellite phone message to the bank’s executives in Edinburgh. After that a special delivery courier was dispatched to take the document to Robertson’s campus at Virginia Beach. None of this was mentioned yesterday afternoon. There was only a terse three-paragraph announcement for the media and the City.

It read: “Dr Pat Robertson and Peter Burt, following a meeting in Boston yesterday [Friday], agreed that the changed external circumstances made the proposed joint venture between Robertson Financial Services (RFS) and the Bank of Scotland unfeasible. Consequently, they agreed that the bank would acquire the interests of RFS in the new bank under the terms provided for in the contract.

“In reaching this agreement Dr Robertson expressed regret that media comments about him had made it impossible to proceed.”

Was that it? Was that all the bank was able to bring itself to say about an incident that has shaken it to the very core?

Back in Edinburgh, the bank’s beleaguered press spokesman Iain Fiddes would only repeat: “No comment” to any request for further information. The same stone-walling approach was adopted by every BoS board director contacted by the Sunday Herald. But this is clearly not going to be enough to satisfy the bank’s customers and shareholders – or the people of Scotland.

A formal apology will have to be made, and it is expected that this will come from Sir Jack Shaw, who assumed the governor’s role last month as a result of the illness of Sir Alistair Grant at the annual meeting next Monday.

The bank has good reason to fear that Robertson might try to take them to the cleaners. The US is a much more litigious society than the UK, and the right-wing preacher could justifiably argue that the termination of the joint venture arrangement will damage his good name.

“The bank deserves credit for getting out of this deal,” said Tim Hopkins, a spokesman for the Equality Network. “But it’s very unfortunate that it should have to pay any money to a man who clearly used it to promote his intolerant brand of politics.”

In the three months since the deal became public, the bank’s staff have been verbally abused, its bank notes have been defaced and its reputation for financial rectitude has been seriously diminished. Several million pounds have been wiped off its stock market value. How could such a well-established Scottish institution – and a FTSE 100 company to boot – find itself at the centre of such a fiasco?

Unfortunately for the bank, the answer lay with those attending last Tuesday’s meeting. Most had played some part in this tale of complacency and incompetence, and have only themselves to blame. It was international general manager McGill and Bill Hendry, the head of American operatons, who first meet Robertson and encouraged the deal. But it was Burt who ensured the board approved it.

In any case, the bank’s diligence – which should have included a trawl on the internet – appears to have been cursory.

If Burt or one of his colleagues had popped down to Waterstone’s bookshop on Princes Street and ordered a copy of one of Robertson’s books – The New World Order, for example – they would have quickly found the measure of the man. The book outlines a fantastical conspiracy theory including links between the United Nations, the Masons and major world events – and argues that a select band who share Pat’s intolerant political agenda are in charge of world affairs.

“There will never be world peace until God’s house and God’s people are given their rightful place of leadership at the top of the world,” says Robertson. “How can there be peace when drunkards, drug dealers, communists, atheists, New Age worshippers of Satan, secular humanists, oppressive dictators, greedy moneychangers, revolutionary assassins, adulterers and homosexuals are on top?”

If you are tempted to read more, the book is available from internet booksellers amazon.com for a £3.37.

Bank insiders say nobody will need to resign over the affair. They also say the bank is preparing to announce another major deal to take the sting out of the episode. But do similar pitfalls lie ahead? There is a real danger that the investors will perceive another deal as being cobbled together just to save face.

And what of Pat Robertson? His spokesman Gene Kapp yesterday refused to elaborate on the termination deal with the bank, but said Robertson had many other projects to keep him busy.

“He’s got a full slate of business deals and is involved in several ventures, including his oil refinery. He is also taking more of a leadership role in his political organisation the Christian Coalition. That, coupled with his daily duties at the ministry, make him a very busy person”.

The Bank of Scotland, meanwhile, has learned a hard lesson about the modern world. Others would be foolish to ignore it.

How the Robertson fiasco hit the bank’s bottom line

The Bank of Scotland yesterday pulled out of its controversial deal with the American television evangelist Pat Robertson to establish a direct telephone banking service in America. The whole affair came to a head last Monday after a video of the American preacher was released. In it he talked of Scotland as “a dark land run by homosexuals”. The bank’s share price tumbled last week as the full force of Robertson’s comments incensed Scots. An emergency meeting in Boston on Friday terminated the business relationship

Copyright SMG Sunday Newspapers Ltd 1999

Short URL: https://www.ianfraser.org/?p=281